This is the second edition of the (P)hotography (E)ssays (N)obody (A)sked (F)or in which I will just write some unwanted essays about photography or (maybe only slightly tangentially) related topics. The full series is listed below.

1/125 of a second

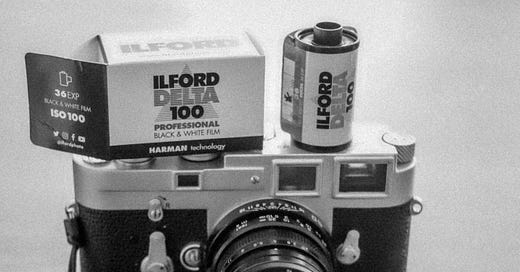

Earlier this year, I bought a perfectly-looking yet defective camera: the legendary Leica M3. In 1958, this camera introduced a lens mount that is still around to this day. This can be seen either as a testament to its indisputable greatness or as an incredibly relentless piece of garbage. There is some debate on that, but I am too ignorant to have an opinion on it, and ultimately I do not care.

Anyway, I saw this M3 for a third of the price because it only had working shutter speeds up to 1/125 of a second. Hence, all faster speeds were not working correctly or working at all. Of course, I bought it in a heartbeat since I was in the market for a rangefinder camera, and this looked like a steal. I usually shoot at 1/125 either way, so to me, it was the deal of the century.

As of now, I have put around ten rolls of film through it, and I can safely say it is my favorite camera of all time. It is the ultimate 50mm shooting experience. Other than that, the effective maximum shutter speed of 1/125 unexpectedly taught me a great deal about light. Especially when considering that this camera is a fully mechanical one, so there is no built-in light meter. Then, exposing correctly is the photographer's problem.

(In)finite possibilities

The analog metering system's bivariate nature (different from the 3-axis digital system1) allows you to always have a scene that can be correctly exposed via subsequent changes in the lens’ aperture and shutter speed.

For instance, if you meter for someone's portrait and the light meter gives you a reading of 1/250 at f/4, you can have an equally exposed photo by adding “one stop2” of light using a slower speed (1/125) and subtracting “one stop” by closing down the lens to f/5.6.

The photo will be exposed exactly the same way, but only the depth of the field will be changed. In this case, the freezing capabilities of the photo will be unchanged since 1/125 or 1/250 are perfectly fine shutter speeds for a non-moving object such as a portrait. Unless your model has to run unexpectedly to the toilet, both 1/125 and 1/250 will give a perfectly still photo.

Potentially, you could also move the speed the other way and create a “dreamy” background by going 1/1000 (minus 2 stops) and opening up to f/2 (plus 2 stops). Anyways, you have a continuous of possibilities only limited by potential camera shake at very low speeds, physical limitations based on the nature of your lens (say you cannot go lower than f/2 when this delish f/1.4-bokeh is needed), or that you are capped at the fastest shutter speeds (some German rangefinders refuse to go faster than 1/1000 if you know what I mean)

The magic number: 1/125

In my limited photographic experience, 1/125 is a very special speed. It is fast enough to freeze slow-moving objects but not fast enough to freeze fast-moving ones. So, it sits in between two worlds: the blurry and the static. Hence, it renders a rather specific look. Also, when shooting while walking, you will get a shaken image depending on how fast you are walking and how you move your camera.

Also, if you are restricted by the fastest speed of 1/125, there will be situations in which there is ONLY ONE aperture on your lens that might give you the correct exposure. For instance, you meter with your trusty light meter, and it tells you that you need 1/500 at f/4, but you can only go up to 1/125, so your only effective option is f/8. Hence, you do not have many options for walking around with a broken camera.

This setting will reduce the infinity possibilities I mentioned to a single aperture number when there is too much light, and you’re capped at 1/125. Hence, I memorized simple yet effective rules that gave me a weird sense of “freedom” from my constant hand-held light-metering psychotic compulsion.

For instance, given that I (almost) always use a 1600 ISO speed film, f/11 is for open spaces on cloudy days and f/8 when buildings are too tall. Then, f/2 is for indoors, and depending on the situation, I would have to go down to 1/30 or less. Everything in between was done by guessing first and then confirming with an external light meter to keep my inner mental peace.

This setup also taught me that the sun was a mortal enemy because if it was out, the camera was out of luck (from the Sunny 16 rule3, I would have needed around 1/1000, so yeah, too bad). This gradually turned into a reflex, so I found myself walking, setting the camera ready to fire depending on lighting conditions, and adjusting it accordingly even though I was not even shooting anything. If I stepped into a darker spot, I opened the lens one or two stops just in case SOMETHING appeared. If I got indoors, I immediately set the lens wide open, etc…

Of course, it did not make me a better photographer, but it essentially gave me some muscular and ocular memory to guesstimate light.

The choice paralysis

Unfortunately, the camera needed to take a break because the lovely winter was over, and the mortal enemy was staying out longer than needed.

After sending the camera to the Leica doctor, I was, of course, in absolute disarray and desolation. Hence, I bought a temporary second body, which I was planning on testing and selling once the M3 was back from the camera doctor. Now, after trying the forbidden fruit of having multiple bodies, I'm not so sure about that, but who knows?

Anyway, this second body had all working speeds, and I felt a rather overwhelming feeling of unlimited choices. Given the extra speeds I felt compelled to use, my rather rudimentary metric system was in danger. However, when facing the endless possibilities again, I gradually learned to transfer the simple set of rules I learned by moving up and down the things I memorized. For instance, if during a cloudy day, I wanted to shoot at 1/500 to freeze the subject, then I needed to add the two stops I lost by the faster shutter speed to my aperture, so from f/11 to f/5.6.

Metering easy mode

To be absolutely fair, cloudy days are probably the easiest days to meter light. The clouds work as a softbox, producing an ideal homogeneously distributed light over the subjects, so it's a “set and forget” kind of situation. Some people call that situation dull and boring, but to me, nothing beats a cloudy day—maybe only a cloudy and misty day or, even better, a cloudy and snowy day.

Sunny days in open spaces are also like that. Actually, those are even easier because you have the Sunny 16 rule, and you know that at f/16, your shutter speed has to be the same as 1/ISO. So, if using ISO 100, then you need 1/100.

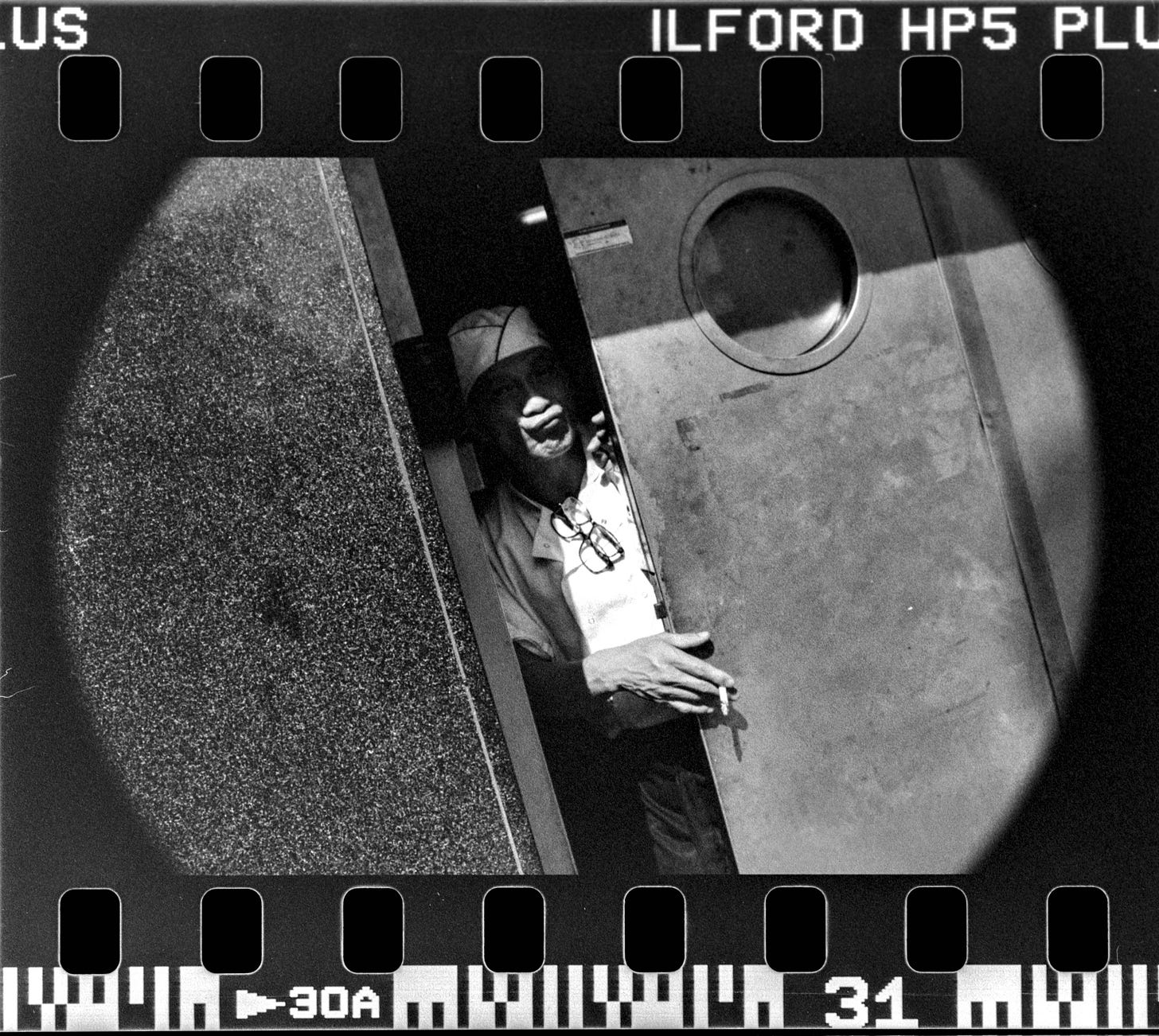

Complicated situations are the moments with harsh lights and shadows that have, in general, two or three stops of light of difference, so you need to make artistic decisions while composing the image. In those cases, considering where you are going to expose (shadows, highlights, or an average of both) presents challenges for the photographer because you not only need to react quickly to the scene unraveling in front of you but also to your exposure.

The photo below is an example of a rapid decision that turned out to be wrong. The subject's face is funny and kind of mysterious, but I was unlucky enough to have half of his face under direct sun and the other half in almost complete darkness. Hence, the dynamic range of this Ilford HP5+ (pushed 2 stops) was not able to retain detail in the shadows.

Hence, aperture priority modes are a blessing in this case, but some purist will detract any sort of machine-induced decision-making in their photographic endeavors as acts of evil or, even worse, weaknesses. I personally think it doesn't matter, as long as the final photo is good, but still, there is a special place in my heart for good photographers who use fully mechanical cameras, especially using them on the streets with fast-moving subjects capturing peak action moments with cameras from the middle of last century4.

Two distinctive worlds below the 1/125 mark

The 60-30-15 trinity

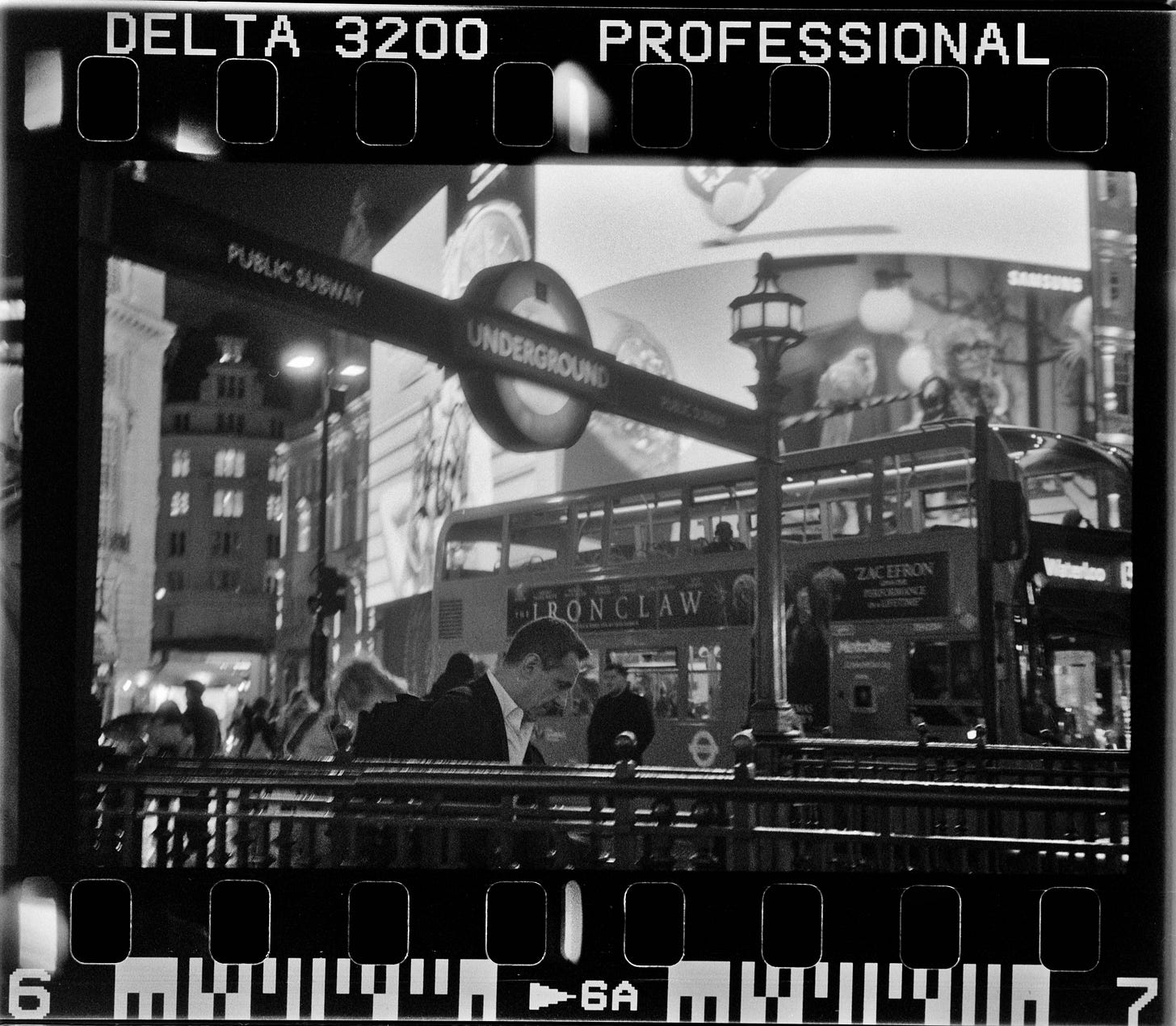

Again, this is based on my extremely limited photographic knowledge, but for me, there are two different worlds below the 1/125 speed. One world is built upon the 1/60, 1/30, and even the controversial 1/15 shutter speeds. Funnily enough, 1/15 is often where photographers might draw a line saying, “I do not go below that handheld” (or without a tripod). Those speeds are workable when standing still or pressing the camera strongly to your face to the point of getting your face red from the pressure.

The shot below was taken either on 1/30 or 1/15. It was taken through a moving bus, and as you can see, there was considerable motion blur. However, the main subject, the person in front of the bus, clearly reflects that it was shot using a lower shutter speed or that the person was sprinting like crazy, which I don’t remember being the case.

Beyond the Super 1/8

If you go lower than that, say 1/8 and below, then things get pretty interesting. The world starts to lose its clear boundaries and you can get a lot of motion blur. Some might like, some might hate, but you know that they say haters gonna hate. This world requires multiple points of contact if shooting handheld. It can be leaning your back against the wall, sitting down, or placing your elbows on top of a steady surface like a table. If you can get that, things get pretty interesting, and depending on things that were moving even slightly, it will blur, and non-moving objects will be tack-sharp, which is a vibe I love. The selfie below and the guy about to punch the punching bag are some examples of this.

Otherwise, you just let the world blur…

A second 1/125 Leica: The Oldcamshop Gods

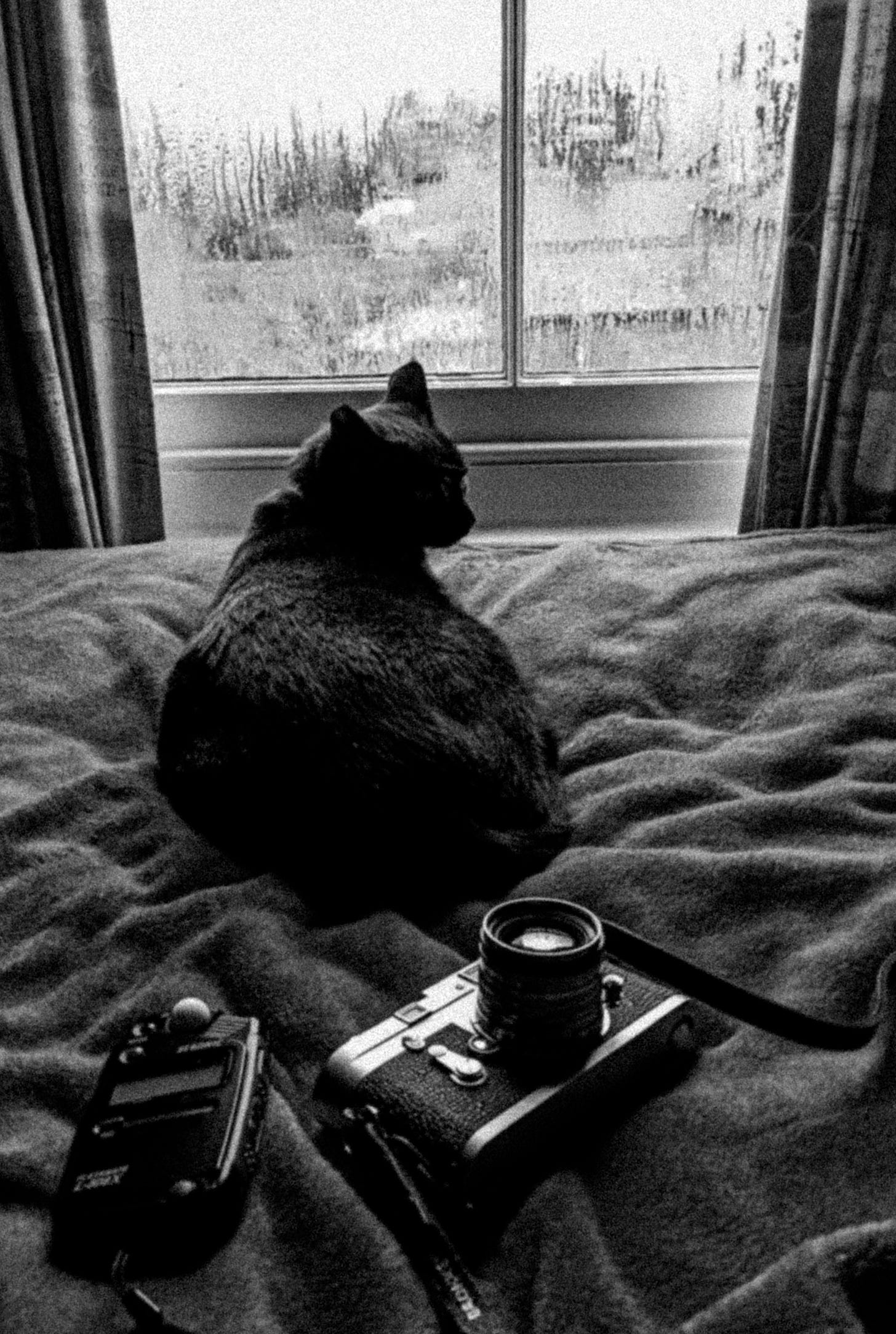

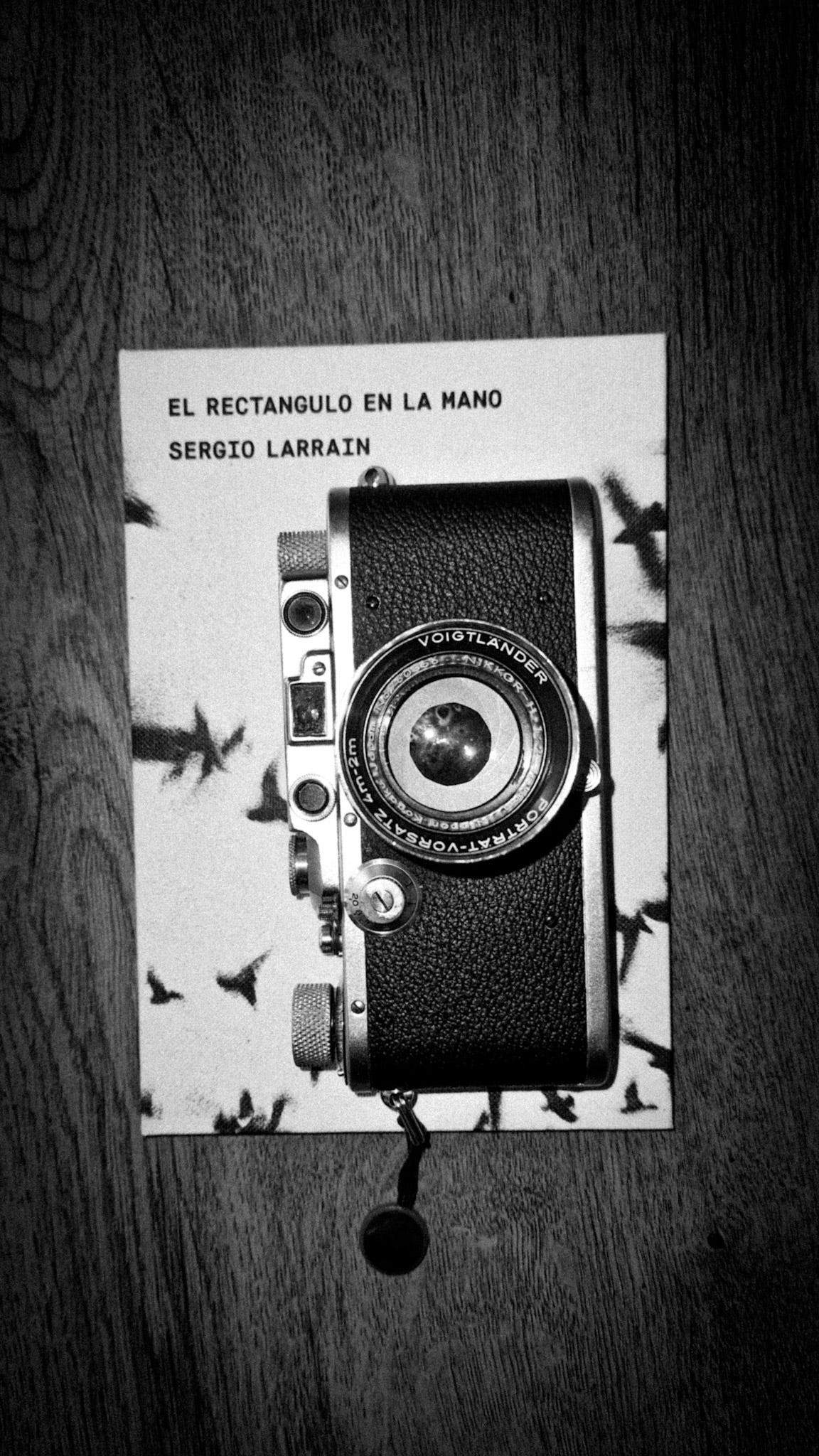

Earlier this year, the awesome folks at Oldcamshop were having a crazy giveaway. They were offering a Leica iiic plus a bunch of film-related clothing. The deal was to submit a photo portraying the ‘ultimate film photographer. ' In all fairness, I am not such a giveaway diehard, but the Leica iiic was the camera that my all-time favorite photographer, Sergio Larraín, used for his entire life, so I said whatever and submitted the image below.

I ranked second on the Instagram giveaway, but regardless, on my next order, a little extra item was included in the box…

I firmly believe this was out of pure pity, and although Dave, the owner, will argue otherwise, I am eternally grateful for this gift because it opened another door for me: the Leica Screw Mount (LTM) system. After using this camera, I started another journey on this system, but this is for another post; for now, some photos of this camera have become my literal number-one go-to.

After the first testing roll, I discovered that it also only worked up to 1/125, but as you might have guessed, this is (in most situations) all I need…

Closing words

I do know why I wrote all that, and I am incredibly surprised if you made it this far. Probably the only important takeaway from this whole thing is that if you see a camera for a great discount, just buy it, and you might end up writing a nonsensical blog post about shutter speeds. Also, special thanks to my mate Axel for his proofreading and clever corrections to this post.

Álvaro Alberto

xoxo

In digital photography, the ISO is, in principle, just another variable that you can play with. When using analog, it is fixed in the camera, so the triangle of exposure is just a single line.

In photographic terms, a “stop” stands for duplicating or halving the amount of light. So when you go from 1/30 of a second to 1/15 of a second, you are literally receiving double the light because you keep your lens open for twice as long. So photographers will say that they moved “added one-stop.” The same light modifications can be made by the aperture. If you open your lens from f/2.8 to f/2, you will receive double the light, too. To be absolutely clear, it is not entirely clear to me who the heck decided that f/2.8 was half of f/2, but trust me, it is.

The Sunny 16 rule basically tells you that for a scene under the direct sun at f/16, your shutter speed has to be the same as 1/ISO. So, if you are using ISO 100 on your camera, then for a day of full sun, you need to always shoot at 1/100 if you are outdoors under a clear sky.

Some names that immediately come to my mind are Damiano Diprima, Tibo De Saegher, and Hashem McAdam.

Really enjoyed reading this, thanks! 1/15th is my favourite speed (digital, with a 25mm lens) - I just love the blur.

Loved this. I thought I had paralysis in trying to get to one camera, one lens! Now take away most of the shutter speeds- what a challenge.